.

.

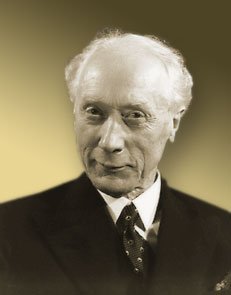

Much has been written, some in great detail, about the life of Frederick Matthias Alexander. Most of Alexander’s life was devoted to teaching others his technique — a technique based on his discovery that his unconscious, habitual interference with his head-neck-back relationship was affecting his overall functioning, and that this relationship could be brought under conscious control. The best account of Alexander’s process of discovery is in his own words in the chapter “Evolution of a Technique” from his book The Use of the Self. Written in 1932, four decades after he began teaching his technique to others, Alexander wrote “Evolution of a Technique” as a testament to how his practical experiences showed that “it is impossible to separate ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ processes in any form of human activity.” (Alexander 1932, 3).

Frederick Matthias Alexander was born in Tasmania in 1869, the eldest of ten children of an Australian farmer. As a child he endured ill health, suffering from respiratory ailments. Early on he demonstrated a love for the arts and studied music and drama in his teens. He developed a passion for the theater. At age seventeen, he left the rugged farm life he grew up with and took an office job with a mining company. After developing a distaste for jobs of the mercantile bent, he determined to become a professional reciter. A professional reciter at that time was a kind of one-man variety show (Alexander 1995, 223). It is noteworthy that Alexander chose a career which made demands upon his respiratory system, a weakness of his constitution that had plagued him with illness during his childhood.

Alexander soon established himself as a well-respected elocutionist. It was not long however, before his career was beset with a major problem. Hoarseness would cripple his speech during recitals, often to the point that he would have no voice left by the end of the performance. His friends informed him that he was audibly sucking and gasping for air while reciting. The treatment of choice by his voice coaches and doctors was rest. During these rest periods he would recover, his voice remaining normal during ordinary speaking. But the problem would insidiously creep back as soon as he attempted to recite. After several repetitions of this pattern, Alexander determined something he was “doing” while reciting was different from his ordinary speaking and this "doing” was causing the problem.

Alexander endeavored to find out what this “doing” was. He put himself in front of a mirror and observed himself first during normal speaking and then in the act of reciting. He noticed that while reciting:

"[he] tended to pull the head back, depress the larynx, and suck in breath through the mouth in such a way as to produce a gasping sound" (Alexander 1932, 9).

Upon further observation, Alexander discovered the same pattern of movement made during reciting was present during ordinary speaking, though to a lesser degree. He realized that his habitual “use” present in everyday activities became exaggerated during times of stress or excitement, such as during a stage performance.

|

F.M. Alexander |

Alexander discovered that his “doing” was a function of unconscious habit in the use of himself in the early 1890s. As he became conscious of what he was doing. Alexander tried to change his habit. He found that no matter how hard he tried, he couldn't stop pulling his head back as began to speak. The old way felt “right” and the drive to move in a way that felt right and familiar was much stronger than his reasoned out new way. This was a critical juncture in the evolution of his thinking. The inability to change what he was doing was a major stumbling block. It was his perseverance that finally led to his discovery that if he first “inhibited” his initial desire to speak, and in that moment give himself directions to allow “his head to go forward and up and his back to lengthen and widen,” he could then stop his old habit pattern. The momentary pause, termed by Alexander as “inhibition,” gave birth to his ability to change himself and later to teach others to change themselves.

Inhibition is the cornerstone of Alexander’s work. Alexander used the term in a very literal sense, defining the act of inhibiting as that of consciously refraining from an act. In order to stop what one is doing, one must be fully conscious of what one is doing. The operative word here is “conscious,” making Alexander's use of inhibition the opposite of that of Freud’s, who used the term to mean “unconscious” repression. Freud believed that one's actions are governed by unconscious or repressed memories; that one is unable to freely choose a course of action because one is unconsciously repressed or inhibited. It is the principle of conscious inhibition that makes the Alexander Technique a potential learning process.

Alexander's discovery has been confirmed by physiologists who have come after him. Dr. David Garlick, an Australian physiologist, describes Alexander's discovery in his study The Lost Sixth Sense in this way:

"Alexander, although not trained as a physiologist, showed a shrewd understanding of how the brain worked. Our consciousness, in the cortex of the brain, is where our will to do something arises. After this the pathways go to centres deep in the brain which form the subconscious or unconscious. If nothing is done to stop existing programs being activated resulting in inappropriate muscle contractions, then a person’s characteristic way of sitting, standing and doing things will occur.

Alexander found the key for stopping these unconscious processes from taking their pre-set paths. Once the impulse has formed in one's consciousness then one stops, or inhibits, the next step in activating the unconscious programs...

Alexander made the significant discovery that the way to interrupt the sequence was to ‘will to do’ something then stop (or inhibit) it which will allow a new ‘program’ to be developed subconsciously while consciously or mentally giving directions ... To decide not to do is an instance of Alexander’s concept of “inhibition.” A physiologist would also use the same term in its scientific sense" (Garlick 1990, 17).

As Alexander practiced the principles of his discovery, the improvement in his public performances was so striking that others began requesting his help. His success in teaching others what he had learned spurred him on to a career in teaching. His pupils began reporting improvements not only in their professional activities but in overall health and well-being as well, and Alexander was eventually teaching people outside of the field of acting. Many of these people were referred by their doctor to Alexander for help with chronic health problems (Alexander 1932, 130).

In 1899 Alexander moved from Melbourne to Sydney, leaving his brother, A.R. Alexander, to teach his technique in Melbourne. A.R. Alexander had become F. M. Alexander's partner after returning home from the Australian gold rush in a weakened condition due to a bout with typhoid.

"F. M., who wanted a partner to help him develop and exploit his discovery, taught A. R. what he had learned. (A. R. maintained that he needed only six lessons.) The two brothers experimented with each other and together worked out various procedures and instructions, which were incorporated into the technique" (Jones 1976, 18).

As his practice grew, F. M. Alexander’s approach and philosophy became more general, changing from that of voice control and breathing, to the control of reaction. Distinguished members of the medical profession supported Alexander, as was able to bring about lasting results in patients with chronic conditions. Upon the urging of a prominent Sydney surgeon, Dr. Stewart McKay, Alexander took up residence in London in 1904, never to return to his native Australia.

In London, Alexander began publishing pamphlets about his technique, which at that point in time he called his “Method of Vocal and Respiratory Re-education.” Between 1906 and 1910, he published several pamphlets on respiratory education (Alexander 1995). He called attention to his work by writing letters to the editors of prominent newspapers, and began attracting the attention of the London medical establishment. In 1910, Alexander published his first book, Man’s Supreme Inheritance. Alexander wrote three more books over the course of his lifetime, each approximately a decade apart.

Alexander first traveled to New York in 1914 at the invitation of Margaret Naumberg, founder of the Walden School. Miss Naumberg was instrumental in introducing Alexander to John Dewey, the famous American philosopher. The two men enjoyed a close relationship throughout the rest of their lifetimes. Dewey began having lessons with Alexander in 1916, a practice that was to continue throughout the rest of his life. He wrote the introduction to three of Alexander's four books. Dewey championed Alexander's work in the educational and scientific community. In spite of Dewey's followers' total misunderstanding and rejection of his belief in the Alexander Technique, Dewey wrote in 1939:

My theories of mind-body, of the coordination of the elements of the self and of the place of the ideas of inhibition and control of overt action required contact with the work of F. M. Alexander and in later years his brother A.R., to transform them into realities (Dewey 1939).

By 1924, F.M. and his brother A.R. were making four month-long sojourns to the U.S. (A. R. eventually settled permanently in Boston in 1933 after the death of his wife.) During the respite between the two World Wars, Alexander and his assistants started a school for children in London. Beginning in 1924, Irene Tasker, a teacher trained by Maria Montessori, ran what came to be known as “the little school,” incorporating teaching children "use of themselves" into the curriculum. The school was evacuated to the U.S. in 1940, with Alexander accompanying evacuees. (Alexander was said to have been on Hitler's hit list as a result of being very vocal about his opposition to der Fuhrer.) Attempts to revive the little school in London after the War were not successful.

It became clear that if Alexander's principles were to stand the test of time as well as accusations that his success was due to personal charisma rather than sound principles, other people would have to be trained to teach the Alexander Technique. In 1931, the first teacher training course was established in London. The format required three years of training — a requirement that has carried through to present-day training courses.

|

F.M. Alexander |

After the publication of his fourth book in 1941, The Universal Constant in Living, Alexander became embroiled in a legal battle in South Africa. In 1935, Alexander's assistant, Irene Tasker had moved to Johannesburg and had begun teaching the Alexander Technique. She had established a large practice which included many prominent South Africans, among them Raymond Dart, dean of the medical school and distinguished Professor of Anatomy at the University of Witwatersrand. Inevitably, she attracted the attention of the medical and educational establishments. In 1941 she met Dr. Ernst Jokl, a German physician and physical educator who was at the time the physical education director for the South African government. Dr. Jokl requested a course of lessons from Tasker. Sensing his skepticism, Tasker refused, maintaining that intellectual acceptance of the principles involved was necessary for lessons to be successful.

In 1943, Dr. Jokl viciously attacked Alexander and his work in print and accused anyone of supporting Alexander of being irrational, neurotic, and mentally unstable. (This may have partially been a result of Alexander’s outspoken anti-German sentiment.) Unfortunately for Dr. Jokl, Alexander's supporters included some highly respected individuals, including the physiologist Sir Charles Sherrington and Sir Stafford Cripps, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the British government. Alexander felt he could not let Dr. Jokl's attack go unanswered and in 1945 brought action against him in South African Court, suing Dr. Jokl for defamation of character. The list of prosecution and defense witnesses read like an international Who’s Who. In December of 1947, Alexander won the case, as well as a later appeal of the case by the defendants (Jones 1976).

Alexander was over eighty years old by the time the legal battles were over. He had suffered a stroke during this time and his recovery and subsequent resumption of his working life was a surprise to Alexander’s medical friends. He spent the rest of his life in London and went on teaching his technique until his death in 1955.

Alexander maintained a love-hate relationship with the medical profession throughout his career. Although never claiming to cure specific diseases, Alexander stoutly maintained that many chronic conditions were the result of patients’ poor use of themselves. He was constantly chiding the medical profession (in print within the journals of the medical profession itself!) for treating symptoms and not taking into account the psycho-physical unity of the patient. Some members of the medical profession were less than tolerant of the views of someone whom they perceived as an arrogant layman. Examples of written exchanges between Alexander and the medical community abound. Many of these exchanges can be found in the recently published volume, Articles and Lectures (Alexander 1995). In spite of his controversial presence, many physicians referred their patients to Alexander.

The Alexander Technique has stood the test of time. It has been a century since Alexander made his discovery about the ability and need for each individual to bring his or her “psychophysical” self under conscious control. Many respected thinkers, including the American philosopher John Dewey, Nobel prize winner Nikko Tinbergen (who in 1973 devoted half of his Nobel Prize acceptance speech to the Alexander Technique), physiologist Charles Sherrington, anatomist Raymond Dart, authors Aldous Huxley and George Bernard Shaw, and many distinguished performing artists, actors, musicians, and dancers. have hailed the Alexander Technique as one of the most important discoveries of recent times.

© 1996 Carol Porter McCullough

Reprinted courtesy of Carol Porter McCullough

References

Alexander, F. Matthias. 1995. Articles and Lectures. Ed.

Jean M. O. Fischer. London: Mouritz

Alexander, F. Matthias. 1918 Reprint. Man's Supreme

Inheritance. New York and London: E.P. Dutton

Alexander, F. Matthias 1932. Reprint. The Use of the Self. Los Angeles: Centerline Press. Original edition, New York: E. P.Dutton & Co., Inc. (Page references are to reprint edition).

Alexander, F. Matthias. 1941. Reprint. The Universal Constant in Living

Dart, Raymond A., 1996. Skill and Poise. Ed. Alexander Murray. London: STAT Books.

Dewey, John. 1939. The Quest for Certainty. New York: G.P. Putnam & Sons.

Garlick, David. 1990. The Lost Sixth Sense: A Medical Scientist Looks at the Alexander Technique. Kensington, Australia: by the author, the University of NSW.

Holland, Mary. 1978. A Way of Working. The Straad 89 (November): 621-629

Jones, Frank, P. 1976. Body Awareness in Action. With a foreword by J. McVicker Hunt. New York: Schocken Books Inc.

Jones, Frank, P. 1997. Freedom to Change. London: Mouritz.

Rolland, Paul. The Teaching of Action in String Playing. Revised edition. New York: Boosey and Hawkes.

Excerpts from The Alexander Technique and the String Pedagogy of Paul Rolland

About the Author

Carol Porter McCullough held advanced music degrees from Florida State University and Arizona State University where she studied viola with William Magers. She was on the music faculty for five years at Illinois Wesleyan University, where she taught viola and was Director of the String Preparatory Department. She played in numerous orchestras, including the Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, and Peoria Symphonies, the Arizona Opera Company and Sinfonia da Camera in Urbana, Illinois. She participated in music festivals across the U.S., including the Luzerne Center for Music, where she was a member of the Luzerne Chamber Players. Carol was a certified teacher of the Alexander Technique, completing her training with Joan and Alex Murray. She conducted workshops for the Alexander Technique for string players, musicians in general and other performing artists.

For more information about Carol McCullough's work, contact Brian McCullough.

“As his practice grew, F. M. Alexander’s approach and philosophy became more general, changing from that of voice control and breathing, to the control of reaction” –Carol Porter McCullough

Alexander Technique: The Insiders’ Guide

Website maintained by Marian Goldberg

Alexander Technique Center of Washington, DC

e-mail:info@alexandercenter.com